The global energy reality

exposes an aspect of the energy crisis: equality denied. Billions in

this planet is the embodiment of this denial, one of the manifestations

of the energy crisis along class line.

“Around 2.64 billion people, 40% of the world's

population,” writes Alejandro Litovsky, “lack modern fuels for cooking

and heating. 1.6 billion have no access to electricity, three-quarters

of them living in rural areas” ( OpenDemocracy , Sept.7, 2007).

He continues: “As decision-makers in Europe and north America wonder

how to reduce energy consumption, massive regions of the developing

world remain literally in the dark. Populations in the energy-poverty

trap – covering vast areas of south Asia and sub-Saharan Africa – are

nowhere likely to influence the accountability of the energy policies of

their governments.”

With the intensification of urbanization the problem

is likely to increase. Current projections show that the majority of

the people in the underdeveloped world will be living in urban and

suburban areas by 2020. A number of the cities in the underdeveloped

countries will emerge as the largest cities in the world in terms of

population. The urban life already is overwhelmed by low-income

population and with the problems pressing them down to dust. This

low-income population has least money to access energy as they have to

live within a precarious life, which is full with hunger, unemployment,

disease, illiteracy. The places they live in don't support human

existence. Lack of safe water and sanitation, insecurity, daily

harassment by tools of rule and indignity are integral part of their

life. In this life, there is no scope to access better energy source.

“Worldwide, hundreds of millions of low-income households,” a World Bank publication informs, lack access to modern energy (electricity and petroleum products), ”

[ B ] ut estimating the figure even

within a few hundred million people is difficult. A common (though

perhaps outdated) estimate is about 2 billion people, a third of the

world's population. Households in many African countries consume little

commercial energy compared with households in the countries of the

former Soviet Union , for example, where the electricity infrastructure

built in Soviet times still connects almost 100 percent of the

population. Low-income households consume a relatively small amount of

energy, and that energy is of low quality. Per capita energy consumption

in South Asia is only 2.6 percent — and that in Sub-Saharan Africa

only 1.3 percent — of per capita consumption in the United States . For

these supplies, survey and anecdotal evidence suggests, South Asians and

Sub-Saharan Africans pay among the world's highest unit costs — and get

some of the world's worst-quality energy. Ugandans spend an estimated

US $100 million a year — an incredible 1.5 percent of GDP — on dry cell

batteries to power radios, flashlights, and other small items. The

average Ugandan household spends an estimated US $72 a year on dry cell

batteries, used in 94 percent of Ugandan households. The cost per unit

of energy consumed works out to US $400 a kilowatt-hour. Ugandans may

spend almost as much per year on kerosene for their lamps. Car

batteries, which cost about US $120 a year to operate, produce

better-quality power at about US $3 a kilowatt-hour. But poor households

often spend a higher share of their income, as in Bulgaria , Jamaica ,

Kazakhstan , Nepal , Pakistan , Panama , and South Africa . More

households use electricity than have in-house water taps or telephones

in countries in Europe and Central Asia and in [some] other countries….

Poor countries consume on a per capita basis, only five percent of the

modern energy consumed by rich countries. Four out of five people

without access to electricity live in rural areas. They include

particularly the rural women and children that depend totally on

traditional fuels. Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia present the largest

gaps in access to energy services: Sub-Saharan Africa has the lowest

electrification rate, with 77% of the population lacking access, or

about 526 million people. In South Asia the equivalent figures are 59%

and about 800 million people. (Rural Energy and Development: Improving Energy Supplies for Two Billion People , 1996 )

More than 95 percent of rural households in Angola ,

Benin , Cameroon , Chad , Congo ( Kinshasa ), Ethiopia , Ghana , Sudan ,

and Zambia among others still use fuel wood and charcoal for cooking.

Many areas of China , India , and Bangladesh also rely heavily on fuel

wood, wood waste, and charcoal for cooking. In China , about 55 percent

of the rural population uses biomass for cooking, as does 87 percent of

the rural population in India . There are more facts provided by the

mainstream that tell the deprivation of the poor in the area of energy.

The Energy and Poverty Reduction – Fact Sheet by the World Bank adds the following:

1.6 billion people lack access to network

electricity.… 1.4 billion people will still lack electricity access in

2030.…2.4 billion people rely on traditional biomass … for cooking and

heating. This will increase to 2.6 billion by 2030 without change in

policies. Poor people in developing countries spend up to a quarter of

their cash income on energy. As of 2004, the richest 20% of the world's

population consume 58% of total energy, whereas the poorest 20% consume

less than 4%. The … poorest people use only 0.2 tons of oil-equivalent

energy per capita annually, while… those earning on average over US

$20,000 a year — use nearly 25 times as much. 1.6 million women and

children die prematurely from indoor air pollution caused by burning

solid fuels in poorly ventilated spaces. 40 million new cases of chronic

bronchitis are caused by exposure to soot and smoke every year. More

than 80% of all deaths in developing countries attributable to air

pollution-induced lung infections are among children under 5 (Energy Poverty Issues and G 8 Actions, Feb. 2, 2006).

There is also wide disparity, according to the World

Energy Council, between the energy consumption levels of the rich and

poor. In terms of electricity consumption, the richest 20 percent uses

75 percent of all electricity while the poorest 20 percent uses less

than 3 percent.

This is also the reality of energy crisis in the

present day world. The billions lacking access to energy services lead

to the “famous” “vicious poverty trap”. It affects health of the poor,

leads to lower productivity, to food insecurity. But the problem is

ignored by the metropolis of the world system.

Unequal distribution of modern energy services and

low level of income in poor countries are two of the major reasons that

constitute the factor leading to poor access to modern energy services.

Lack of or poor infrastructures in the poor countries, lack of resources

to develop the required infrastructure, and biased institutional and

legal framework also have their share in creating the problem for the

poor. Absence of political commitment in favor of the poor is the

foremost problem that limits the access to modern energy by the poor.

The political commitment is biased, tilted to the rich. It follows the

class line.

The poor households in the underdeveloped countries

mainly use firewood, dung, tree leaves, crop residues, and in some

cases, charcoal. The World Energy Outlook 2006 estimated that

$8 billion (including capital and fuel) a year up to 2015 would be

required for 2.5 billion people for their switching over to liquid

petroleum gas for cooking.

The poor pay a high price for the energy they use:

in terms of cash, labor, time, and health. They spend a much greater

proportion of their income on energy than wealthy people. In Burkina

Faso, a survey found, the poor devoted 5.6 percent and 1.3 percent of

their income to firewood and kerosene respectively while in Guatemala

and Nepal, firewood expenditure for households in the poorest quintile

accounts for 10-15 percent of total household expenditure (R Heltberg, Household Energy and Energy Use in Developing Countries, A Multi-Country Study, 2003).

Studies on Bangladesh environment found that the

availability of biomass has decreased. This has increased the hardship

of the poor, especially of the women. They have to spend more time to

collect biomass. The slum dwellers in Dhaka informed that they cooked

once or twice a day instead of three times. That was the way they

“innovated” to economize the spending on fuel. The price of firewood

compelled them to follow the method though it was not good for food

quality and health. The participants in the study suffered from health

problems due to smoke from firewood. Villagers from different parts of

the country also informed that the availability of biomass decreased.

The changed reality taxed them in terms of labor, wage lost, and

hardship. Consequently, this touches the limits of nutrition, household

income, and productivity. The women had to bear most of the burden as

they collected fuel for their families. Sometimes, an entire day was

spent by the earning member of a family for collecting firewood

(Farooque Chowdhury, “Urban Poor: Never-ending Quest for Energy”,

“Scarce Fuel: Growing Scarcer”, and “Fuel, Firewood and Ghatail” in People's Report 20002-2003: Bangladesh Environment , UNDP, 2004).

These are the people who have been and are being

pushed down to energy poverty that constitutes one of the elements of

energy crisis. In ultimate analysis, these people have been kept

confined within an inefficient system, which they have not organized.

Rather, the system constructed by the dominating capital has been

imposed on them. The system is so much inefficient that it cannot

utilize the labor and creativity of these poor people. That means: the

system lacks the capacity to tap energy.

The disparity is not only limited among the rich and

the poor. Wide variations are there in the levels of energy

consumption, according to the Human Development Report 2007/2008,

between industrialized and the underdeveloped countries. Per capita

energy consumption in North America is about 18 times that of Africa and

four times the world average.

Energy poverty is defined as the “inability to cook

with modern cooking fuels and the lack of a bare minimum of electric

lighting to read or for other household and productive activities at

sunset” (UNDP 2005). By this definition, the 2.5 billion people relying

on biomass for cooking and the 1.6 billion people with no access to

electricity could be classified as being energy poor.

Originating from the UK and Ireland 's grassroots

level environmental health movements in early 1980s the concept of

energy poverty or fuel poverty, has gained in importance. “With the

energy crises of 1973/74 and 1979,” the World Energy Council said,

“low-income households experienced difficulties with increased heating

bills. The fuel poverty concept is an interaction between poorly

insulated housing and inefficient in-housing energy systems, low-income

households and high-energy service prices. At the beginning of the 21st

Century, the British Government set up a strategy on fuel poverty aiming

at eradicating this phenomenon by 2010 … for vulnerable households and

by 2016 for all English households. According to the British standard

definition that was adopted, a household is poor in fuel if it needs to

spend more than 10% of its income on all fuel use to heat the home to an

adequate standard and to meet its needs for other energy services

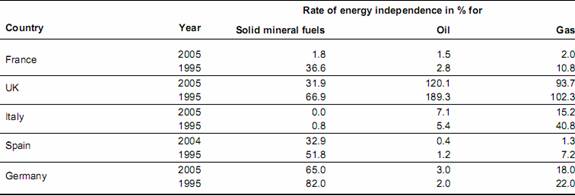

(lighting, cooking, cleaning, etc.).” (World Energy Council, Europe's Vulnerability to Energy Crisis ,

2008) The report added, “In England … the number of households poor in

fuel decreased from 5,1 million in 1996 to 1,7 million on 2001 and to

1,2 million on 2004.” Table 1 provides a picture of fuel poverty in a

number of European countries during the period 1994-'97. Portugal had

the highest percentage of households defined at fuel poverty while

Denmark had the lowest.

Table 1: Households Defined at Fuel Poverty, 1994-1997

Used by permission of the World Energy Council, London , www.worldenergy.org

In the US , the number of households in fuel poverty was 15.9 million (“Fuel Poverty in the USA ”, Energy Action , March 2006).

There is difference between the fuel poor in an

advanced capitalist country and fuel poor in a poor country. The level

of hardship between them also differs. But that does not nullify the

reality of inequality in distribution. With the financial and food

crises the suffering has increased. For the homeless and the unemployed

in the US , the suffering is more. A number of news reports were

dispatched by news agencies that the unemployed in the US were finding

it hard to pay energy bills. In extreme weather in parts of the US ,

like all places in the world, the suffering increases.

While the energy poor is one aspect of the crisis there is over-consumption that has contributed to the crisis.

The type and volume of energy used by households

differ from country to country. Income levels, natural resources,

climate and available energy infrastructure determine these.

Typical households in the OECD countries consume

more energy than those in the non-OECD countries. The OECD households

with higher income can afford larger homes and purchase more

energy-using equipment. In the US , GDP per capita in 2006 was about

$43,000 (in real 2005 dollars per person), and residential energy use

per capita was estimated at 36.0 million Btu. On the other hand, China

's per-capita income in 2006, at $4,550, was only about one-tenth the US

level, and residential energy use per capita was 4.0 million Btu.

Poorer households in Asia , Africa and Latin America earn less, and

consume less energy.

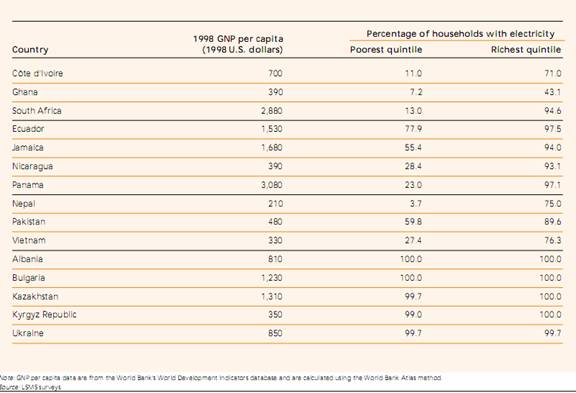

Table 2 from a World Bank publication (from the

section by Alan Townsend, “Energy access, energy demand, and the

information deficit”) shows that disparity between the rich and the poor

in electricity use is great. Disparity in this area is nil in Albania ,

Bulgaria , Kazakhstan , Kyrgyz Republic , and Ukraine while it is great

in other countries including Ghana , South Africa , Nicaragua , Panama ,

Nepal , and Vietnam .

Table 2: Disparity Between the Rich and the Poor in Electricity Use

Source: the World Bank publication, LSMS survey in 15 developing countries

The US consumes most energy: 8.0 toe/person/year,

followed by India and China with an average energy consumption of 7.3

toe per person per year each. On per capita basis, however, Canada

consumes the most energy in the world. Its per capita energy consumption

is 6.4 times the world average while that of the US is 5.1 times and

Western Europe 's is 2.3 times the world's average (P O Pineau, Electricity Subsidies in Low Cost Jurisdiction, The Case of British Columbia ( Columbia ) ,

2006). Italy consumes the least energy among the industrialized

countries (3.1 toe per person per year). Africa 's average energy

consumption only 0.14/person/year, a ratio of 1:57 , compared to the US .

Average energy consumption in Bangladesh is only 0.08 toe per person

per year, which is a ratio of 1: 100 when compared to the US that uses

about fifteen times more energy per person than does a typical

underdeveloped country. While the US share of the world's population is

only 4.6 percent, it accounts for 24 percent of the world's energy

consumption and over 30 percent of GDP. But the least developed

countries with 10 percent of the world's population account for about 1

percent of energy consumption and a mere 1 percent of the world's GDP

(Huq, et al. 2003). The energy situation Africa faces is a

mixture of contradictory reality: while the continent desperately needs

energy for economic growth and poverty reduction, it is a net exporter

of commercial energy. Africa is home to about 7 percent of the world

commercial energy, but it accounts for only 3 percent of global

commercial energy consumption.

Energy use in the residential sector in 2006, according to the IEO2009 (International Energy Outlook, 2009) , accounted for about 15 percent of world delivered energy consumption. Larger homes, the Outlook

said, need more energy as these homes tend to use more energy-consuming

appliances. On the contrary, smaller homes usually need less energy as

the smaller homes have less space to be heated or cooled, produce less

heat transfer with the outdoor environment, and the appliances used in

these homes are smaller. For example, residential energy consumption is

lower in China than in the US . The average residence in China currently

has an estimated 300 square feet of living space or less per person

while the average residence in the US has an estimated 680 square feet

of living space per person. The commercial or the services and

institutional sector include businesses, institutions, and organizations

providing services (schools, hospitals, water and sewer services,

theaters, museums, art galleries, sports facilities, stores, hotels,

restaurants, correctional institutions, office buildings, banks), and

traffic lights. Economic activities and disposable income going to

higher levels lead to increased demand for energy as demands for office

space, space for business, hotels, restaurants, and facilities for

cultural and leisure activities increase. Energy use per capita in the

commercial sector in the non-OECD countries was much lower, 1.3 million

Btu in 2006, than in the OECD countries, 16.3 million Btu. The US is

the largest consumer of commercially delivered energy in the OECD and

remains in that position throughout the projection, accounting for about

44 percent of the OECD total in 2030.

The deeper, the keener observation on the issue, the

more inequality gets exposed. The inequality in energy distribution

comes from the unequal ownership of the energy resources, and is part of

the unequal world system.

The inequality aspect should have the same, if not

more, importance as other burning aspects of the energy crisis.

Rectifying the inequality is one of the ways to face the crisis.

Participation of people strengthens steps to face the crisis. But, shall

there have any rational and moral standing if people are asked to

contribute to/sacrifice for/play role into facing the crisis if they

have no or little or unequal access to the energy resources? The crisis

is not their creation. So, one of the first steps to face the energy

crisis should be replacing the unequal energy distribution system with

an equal and equitable energy distribution system. The other major step

should be to inform people about the crisis and inequality so that

people get aware. Awareness facilitates people getting organized and

taking creative initiatives, and a collective force thus gets mobilized

to face the crisis.

[ This section, modified and elaborated for

clarity and completeness, is preceded by two parts of the chapter, “

Energy Inequality and Energy Poor” in The Age of Crisis (2009) by

Farooque Chowdhury, a Dhaka-based freelancer. For easy identification,

the section can be considered as part 3 of the chapter. ]